William Wordsworth On Writing through Imposter Syndrome

The power of "spots of time" to push us beyond our writing barriers and blocks when we are wrestling with big ideas.

Over the past several months I have been tinkering away at a book proposal—or, I should say, at two book proposals. The first one took me around three complete rewrites to get it into a state I was happy with. But when I had the chance to speak to an editor about this “final” version, she pointed out several problems with it, after which I began to suspect that I had conceived a project that required more intelligence and writing talent than I happen to possess.

Fortunately, good fortune rode in to save me from despairing and putting my notebook and pen out to pasture. At almost the exact time I finishing that proposal, a different editor reached out to me and suggested a potential new book topic I should consider, one that spoke to one of my longstanding passions. I pivoted immediately to working on that one—only to find myself writing and chucking version after version of it. That revision process remains in flux.

I was lamenting this whole tortuous process to another academic recently, and she responded by saying that while she was sorry I was having so much trouble with my writing, she received some comfort from learning that a well-published author still struggles in the ways I was describing. She was in the habit of assuming that her ongoing struggles as a writer predicted a bleak future for her authorial career.

Which I totally get, because I had just felt those same emotions of comfort as I was reading William Wordsworth’s The Prelude, a multi-volume poem which begins with a disquisition on the shallowness of his talents in the face of his ambitions.

That’s right—William Wordsworth, the most famous of the Romantic poets, who helped launch a revolution in English poetry and served as England’s poet laureate for the last seven years of his life, had imposter syndrome, just like the rest of us.

I am a late-blooming devotee of Wordsworth’s poetry. Although my academic specialty was British novels of the 20th century, I often taught the second half of the British literature survey, which covers the period starting around 1800 and continuing to the present day. Whenever I taught that survey, I felt most comfortable with the literary works from the late 20th century, but over the years I found myself gravitating more and more to the earliest poets on the syllabus. Eventually, after many iterations of teaching the course, I realized that I had fallen in love with Wordsworth.

If you took English classes in high school or college, you probably read some of Wordsworth’s poetry. If you read him in high school, you might have been assigned some of his nature lyrics, which reflected his convictions of a deep spiritual presence connecting the human and natural worlds (i.e., “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”). If you read him later in your schooling, you might have encountered his most well-known poem, “Tintern Abbey,” which I found boring as a young man but have come to appreciate more every year I have returned to it.

While posterity seems to have judged Wordsworth’s lyrical poetry as his greatest legacy, no single work of his occupied his attention more than the thirteen-book poem1 that he began composing in 1798 and kept on tinkering with until his death in 1850. It wasn’t published until a few months after he died, at which point his widow gave it the final title The Prelude, or, Growth of a Poet’s Mind: an Autobiographical Poem. As the subtitle implies, the poem covers key periods of his life, including his childhood in England’s Lake District and a walking tour of the Alps he conducted as a young man.

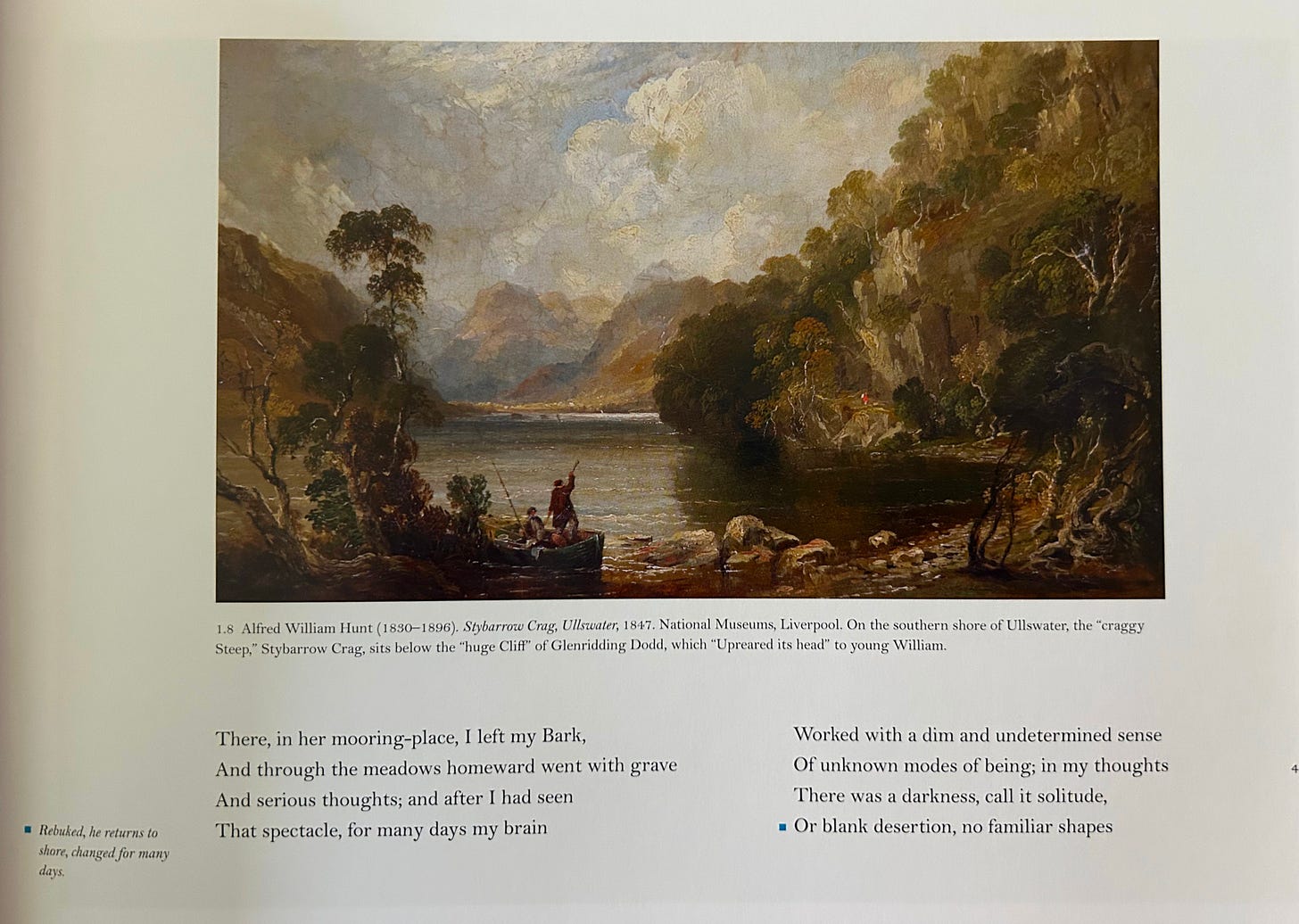

Even with my love of Wordsworth’s poetry, the length of The Prelude had always proved too daunting for me, and I had never attempted to read it until very recently. What tipped me into committing to a full reading of it was a gorgeous illustrated edition published by Brandeis University Press in 2016. Almost every page of the book resembles what you see below—a contemporaneous work of art or sketch that helps the reader envision the world that Wordsworth describes.

The book takes the form of a coffee-table monograph, and its size and the quality of the paper make it a very substantial object, which pairs well with our sense of Wordsworth’s firm position within the pantheon of the world’s greatest poets in the English tradition. Which makes it all the surprising when you discover, in the first book of the Prelude, Wordsworth offering an eloquent rendering of the self-doubts that beset him as he undertakes his poetic autobiography. In the lines below, he describes a frustrating perfectionism continually thwarted by his lack of talent, intelligence, and industry:

Far better never to have heard the name

Of zeal and just ambition, than to live

Thus baffled by a mind that every hour

Turns recreant to her task, takes heart again,

Then feels immediately some hollow thought

Hang like an interdict upon her hopes.

This is my lot; for either still I find

Some imperfection in the chosen theme,

Or see of absolute accomplishment

Much wanting, so much wanting in myself,

That I recoil and droop, and seek repose

In listlessness from vain perplexity,

Unprofitably travelling towards the grave,

Like a false steward who hath much received

And renders nothing back.

I often find my thoughts and experiences mirrored in works of literature—isn’t that why we read them?—but this one feels a little too on point. “A mind that every hour/turns recreant to her task”? Check. Finding imperfections in a book proposal, and giving up on it because I’ll never bring it to a level of absolute accomplishment? Check. Stepping away from a piece of writing in “listlessness from vain perplexity,” and then never returning to it? And check again. “Unprofitably travelling towards the grave?” Well, maybe not that one.

I’m not sure I have ever met a well-published writer who hasn’t experienced these feelings at some point in their career, or in the pursuit of a specific project. And if it helps other writers to know that, I’m happy to reveal their presence in my writing life.

But of course we also have the published works of those same writers, which means that they have discovered means of overcoming these debilitating emotional blocks. In the case of The Prelude, we do have this stark rendering of Wordsworth’s imposter syndrome, but we also have the twelve books that follow, not to mention the many other poems he wrote and published in the remainder of his career. What can we learn from writers who move beyond that first stumbling block? And, especially for the purposes of most of my readers, what can academics learn for their writing practices from William Wordsworth’s movement from listlessness to completion?

Wordsworth shows us one route in the final lines of this same first book of The Prelude. After the first few hundred lines of the poem, in which he largely reflects upon the project itself and its dim prospects, he veers from abstraction and begins narrating his experiences as a boy. Nothing particularly dramatic is recounted; he conveys an impressionistic account of his childhood in the Lake District: scrambling over hills and cliffs, ice-skating on the lake with playmates, sitting by the fire in the cottage. As the first book comes to a close, he seems to stand back to note that—almost with an air of surprised bemusement—that recounting these humble scenes has revived his commitment to the project itself:

One end hereby at least has been attained,

My mind hath been revived, and if this mood

Desert me not, I will forthwith bring down,

Through later years, the story of my life.

The spur to his writing that Wordsworth describes here contains a lesson for those moments when writers feel like their writing project looms too large before them, and their ambitions have o’er reached their talents. When the ideas and concepts and theories are too jumbled in our brains, and we just don’t see a clear path from the neurons to the words on the page, we can follow Wordsworth’s lead with this simple act: write a scene.

Scenes grounded in time and place drove much of Wordsworth’s writing, as the editors of the The Prelude point out. His poetry contains much philosophical musing and argument, but it always emerges from scenes. Wordsworth famously called these “spots of time” which are instrumental in forming our growth—not only our growth as humans, but the growth of our ideas. In their pitch for the relevance of The Prelude to readers today, the editors argue that as we read it, “we come by extension to read the places in our own lives and the growth of our own spirits”—in other words, if we follow Wordsworth’s lead, we will pay better attention to the key scenes in our lives, and the role that “situated” experiences play in the formation and development of our ideas.

Whatever you might be working on, you probably have a memory etched in your brain when you first found yourself struck by a question, a problem, an insight, or a powerful emotion connected to your subject matter. These are the idea’s “spots of time,” its connections to situated experiences. When you’re stuck, when you’re demoralized, when you feel like you’re traveling unprofitably towards the grave in the pursuit of a recalcitrant idea, stop and describe that spot of time. Do it with as much detail as you can: write down whatever images, words, and emotions that stick with you from that moment. What did you learn in that spot of time? Why has it stuck in your memory? And whatever it meant to you in the moment, what more could it mean to you now?

In The Prelude, as in my own writing, surfacing and describing spots of time serves as a bridge from inaction to movement. Instead of staring at the screen, I am writing. To be sure, many of the scenes I have written for my books and essays end up in the scrap heap. I am not enough of a Wordsworth scholar to say this for certain, but his long history of revising the “The Prelude” would certainly suggest that plenty of scenes from his own life were drafted and ended up in the prose refuse pile. So it goes with any good piece of writing.

And perhaps even with good book proposal. Over the course of drafting this essay, I have been thinking about a conversation I had with a colleague last week in a coffee shop on campus. I’m thinking about the cup of tea I had, the book and notebook on the table between us, the students all around us staring into their laptops and phones, and the book I want to write about the fate of book-reading in today’s world.

Will that scene make into the final version of the proposal? Maybe, maybe not. I’m going to write it anyway.

Because the poem took shape over many years and iterations, it has appeared with different numbers of books. The Brandeis University Press edition I am describing here uses the 1805 version, which contains thirteen books.

I love Wordsworth’s Prelude and, on the rare chance I get to teach it, I talk about Wordsworth spending that first Book trying to get over his writer’s block (everyone can relate to this!). If only we could all use his method of spending days wandering lonely through England’s Lake District, napping under trees, to gain our inspiration. :-) I am grateful my Wordsworth & Byron grad seminar professor, over 25 years ago, assigned us the 1850 Prelude to read in its entirety. Otherwise I may never have read it.