On the Power of the Menial, the Boring, the Painstaking . . .

What happened when I embraced a very boring learning task. Or: When philomathy isn't quite so philo.

In the Afterword of my new book, Write Like You Teach, I introduce a word that I discovered during my recent study of ancient Greek: philomath. You might know the word polymath, which describes someone who knows a lot of stuff. It combines the root for many (poly) with a root that refers to learning (math). The word philomath, with its initial root coming from one of the Greek words for love (philo), refers not to someone who has already learned a lot of things, but who enjoys the process of learning. Doesn’t matter what they are—the learning act itself brings them joy.

In the book’s Afterword I do this little etymology just to note that when I discovered the word philomathy, I realized that it had been the keyword of my life. Nothing brings me more joy than the prospect of new learning, the learning process itself, and the satisfaction of having gained new knowledge or skills. In the final paragraphs of the book I speculate that most of my readers, largely academics, are also philomaths, and thus our writing can extend the gift of philomathy to our readers.

But this week I have been thinking about the features of learning which are not enjoyable, and that’s what I want to address in this month’s essay. In my LinkedIn feed, which seems largely populated by educational innovators and proponents of artificial intelligence, everyone seems to be promising to make learning more enjoyable, more creative, more innovative, more meaningful, less boring, less traditional, less analog (you get the idea). I sometimes feel like the cranky old man of higher education development these days, because I just keep thinking about the fact that deep learning will always entail periods or practices which are difficult, boring, painstaking, time-consuming . . . (you get the idea).

The rest of this essay essentially serves as a single illustration of what happens when we prioritize the painstaking stuff, and I hope my single story will inspire you to reflect upon your own experiences either as a learner or as a teacher of learners. What was the painstaking stuff when you were studying and learning the fundamentals of your own discipline? Do you feel like that painstaking work helped you get to where you are now? Would you have achieved what you have achieved without having done some of what one of my colleagues calls the “donkey work”?

My Single Story

When I wrote that Afterword for the book, I was still in the early stages of re-learning Greek. I had studied ancient Greek both in high school and college, and had returned to it here and there in the next thirty years. After my transplant and stroke, I remembered how much joy I had experienced in my language learning years, and I decided to fully re-commit to learning Greek, which had been my favorite of the languages I had attempted. I bought some textbooks, began making flashcards, got an app and found a good video series, and generally tried to have Greek study time every week.

Looking back at that period, I would describe my approach as haphazard and/or lackadaisical. I did put in plenty of hours, but I was not really making much progress. This lack of full commitment (and of progress) started to annoy me, because I have studied learning for too many years to approach something that mattered to me in such a desultory fashion.

At the start of this summer, then, I decided to commit fully. First, I hired a tutor. I connected with a graduate student in Classics, and we agreed on a simple plan: we would pick a text, and every two weeks we could sit together on Zoom while I read it aloud and tried to translate, while he guided me and answered my questions. In the intervening days, I would fully commit to doing all of the activities recommended in my textbook to get me up to speed as quickly as possible.

Second, I decided to get up every day at 7:30 every day and start the morning with thirty minutes of Greek study. (Side note: This has been life-changing. I am not a morning person, so historically I would get up at 8:00 or 8:30, mope around having tea and breakfast, read my email and news feeds, and generally postpone the time when I have to start working. By contrast, a half-hour of philomathy in the morning launches me into the day in a powerful way. I go to bed looking forward to the prospect of learning Greek in the morning.)

But.

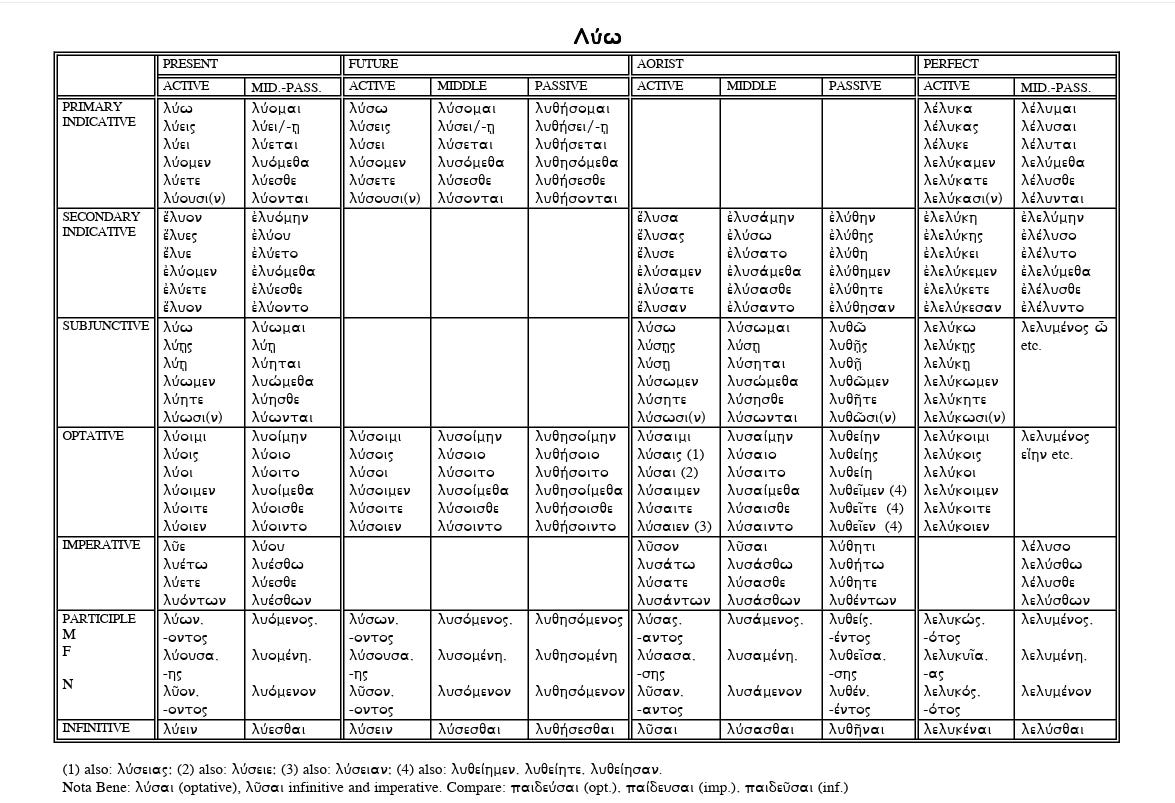

While I enjoy the process of learning Greek in a general way, and learning languages in particular, some parts of it suck. In ancient Greek, as in Latin and plenty of other languages, the verbs and nouns change according to their role in a sentence. For example, the verb for “loosen/release” has a different form if you are saying “I loosen,” “you loosen,” “he/she/it loosens,” “we loosen,” “you (plural) loosen,” and “they loosen.” And that’s just for the present tense! The forms are completely different for the other tenses (future, imperfect, etc.), for active and passive voices, and so on. Below you can see a chart from the classics department at the University of Chicago which shows all the possible conjugations for this single verb “loosen”:

Nouns work in the same way; the word has a different form if it’s the subject of the sentence, the object, an indirect object, or the object of a preposition. Noun forms are slightly simpler than verbs, but there are still three different declensions of nouns, each of which have their own patterns, as well as three genders in all declensions: masculine, feminine, and neuter. With the both the nouns and verbs, the declensions and conjugations do indeed follow patterns, so when you have memorized those patterns, you can apply them to most words, although there are plentiful exceptions you have to memorize.

In my lackadaisical days of learning Greek, I would do the easier textbook exercises on the forms, and also used an app that would quiz me on the forms. These strategies did help. But I never really got the grasp on the forms that I wanted; translating sentences often went slowly and painfully because I had trouble recognizing the verb or noun form and had to stop and look it up. I knew full well that this was happening because I had not really done what the textbook was telling me what I should do: write them out multiple times, in sequence, to fully commit them to memory.

Why? Because donkey work sucks; that’s why we avoid it. It’s why we started using donkeys in the first place. Even though I knew it would help me, I keep putting it off and doing the things that felt easier, like watching the fun video tutorials.

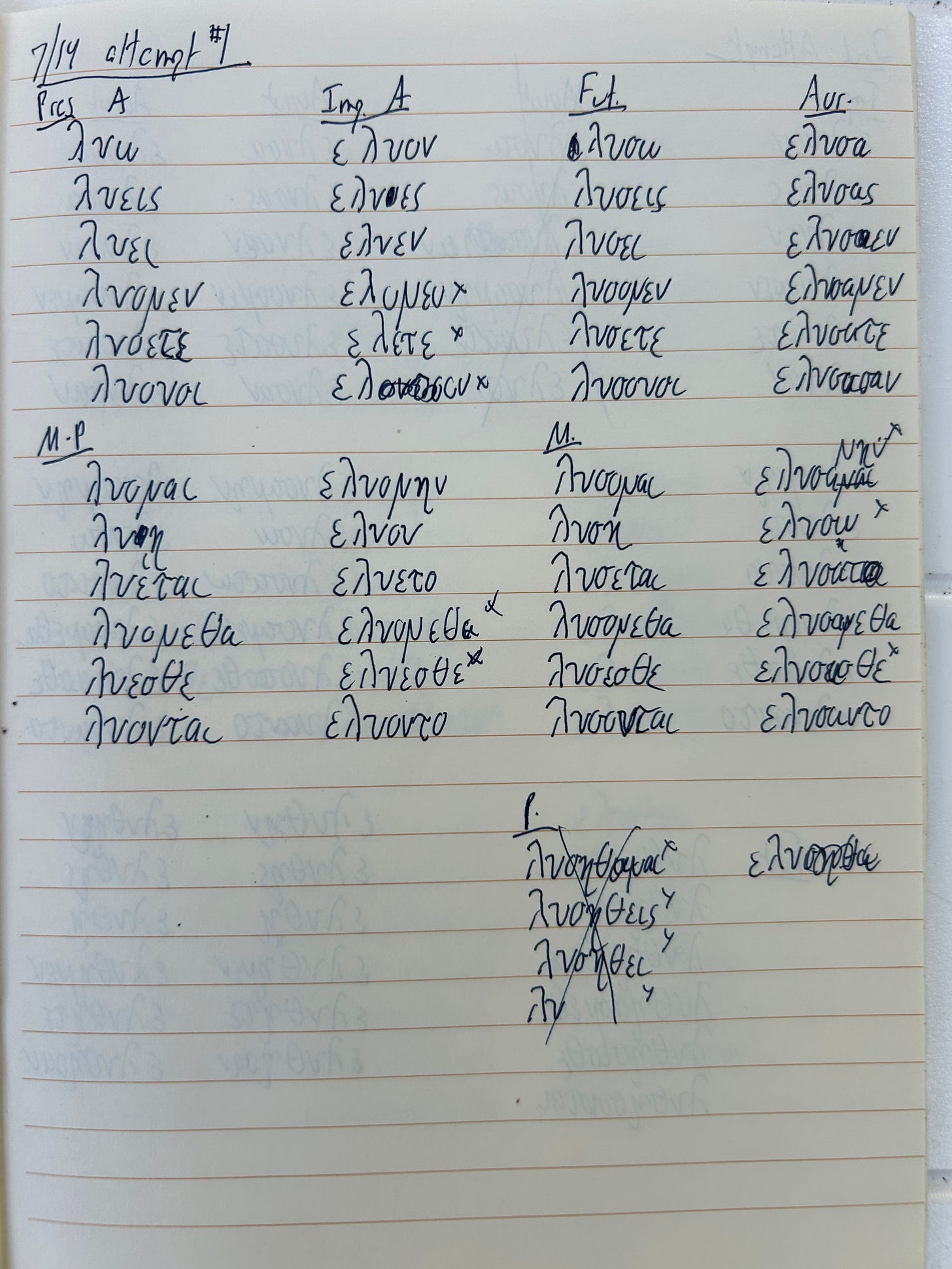

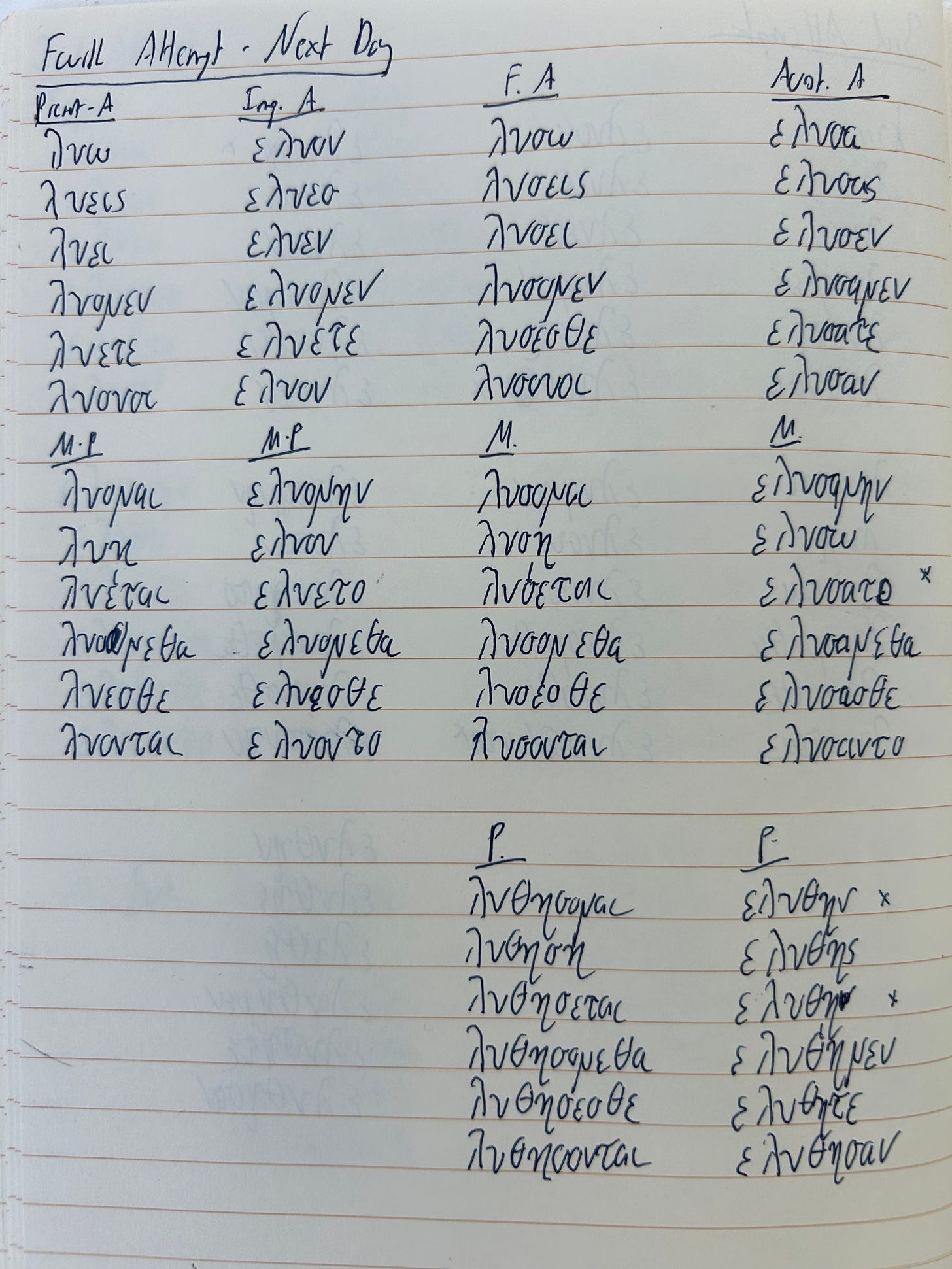

A few weeks ago, I steeled myself up and decided I would spend at least one or two of my thirty-minute sessions seeing if I could write out all of the conjugations of all four verb tenses I know at that time. Without getting into detail about how many words there should be, you can see my first attempt below, which has both gaps and wrong guesses (which are marked with a tiny x):

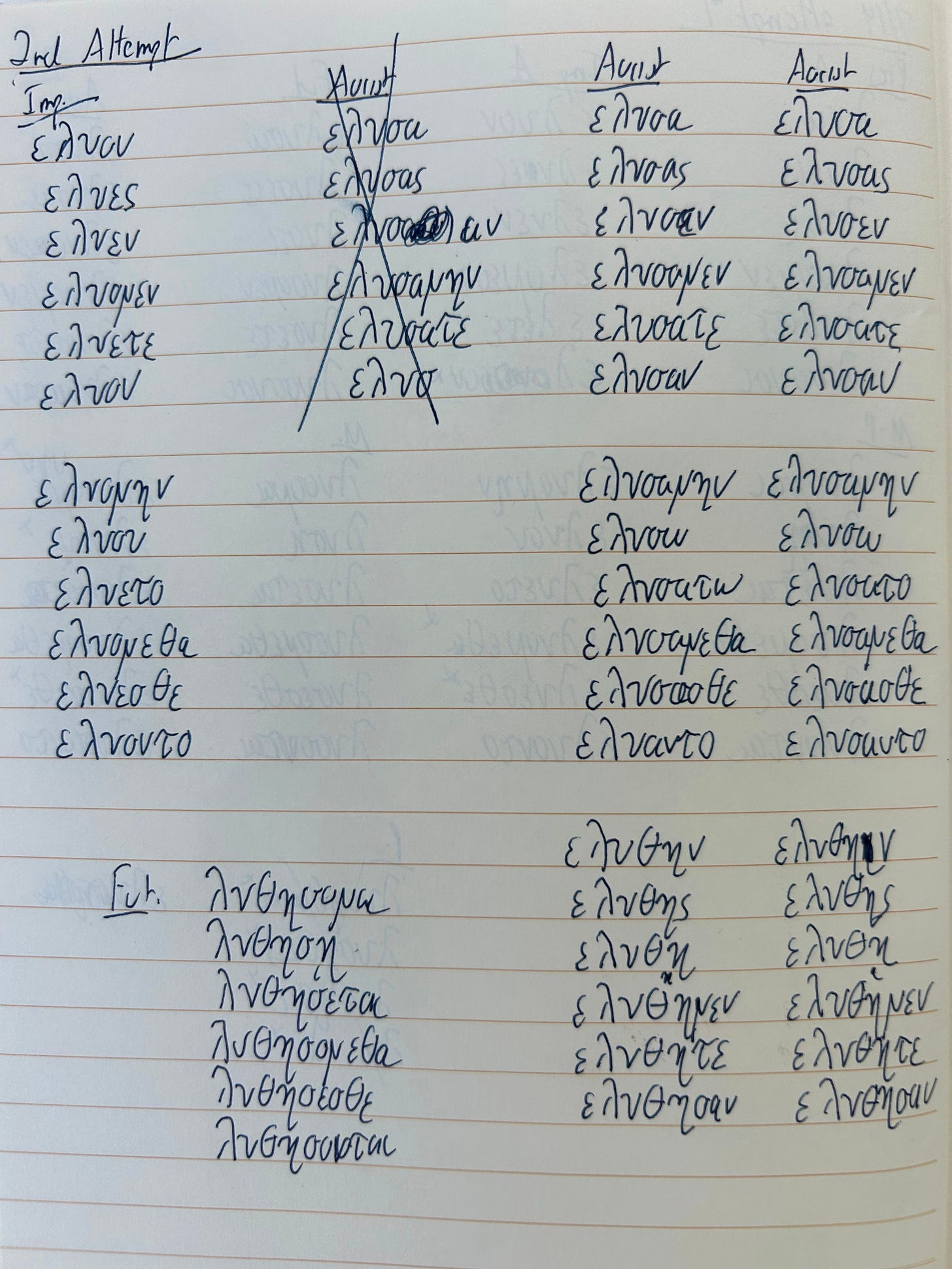

After that first attempt, my second and third attempts were partial ones, in which I just wrote out that tenses that I was weakest on, and didn’t write out all the whole set:

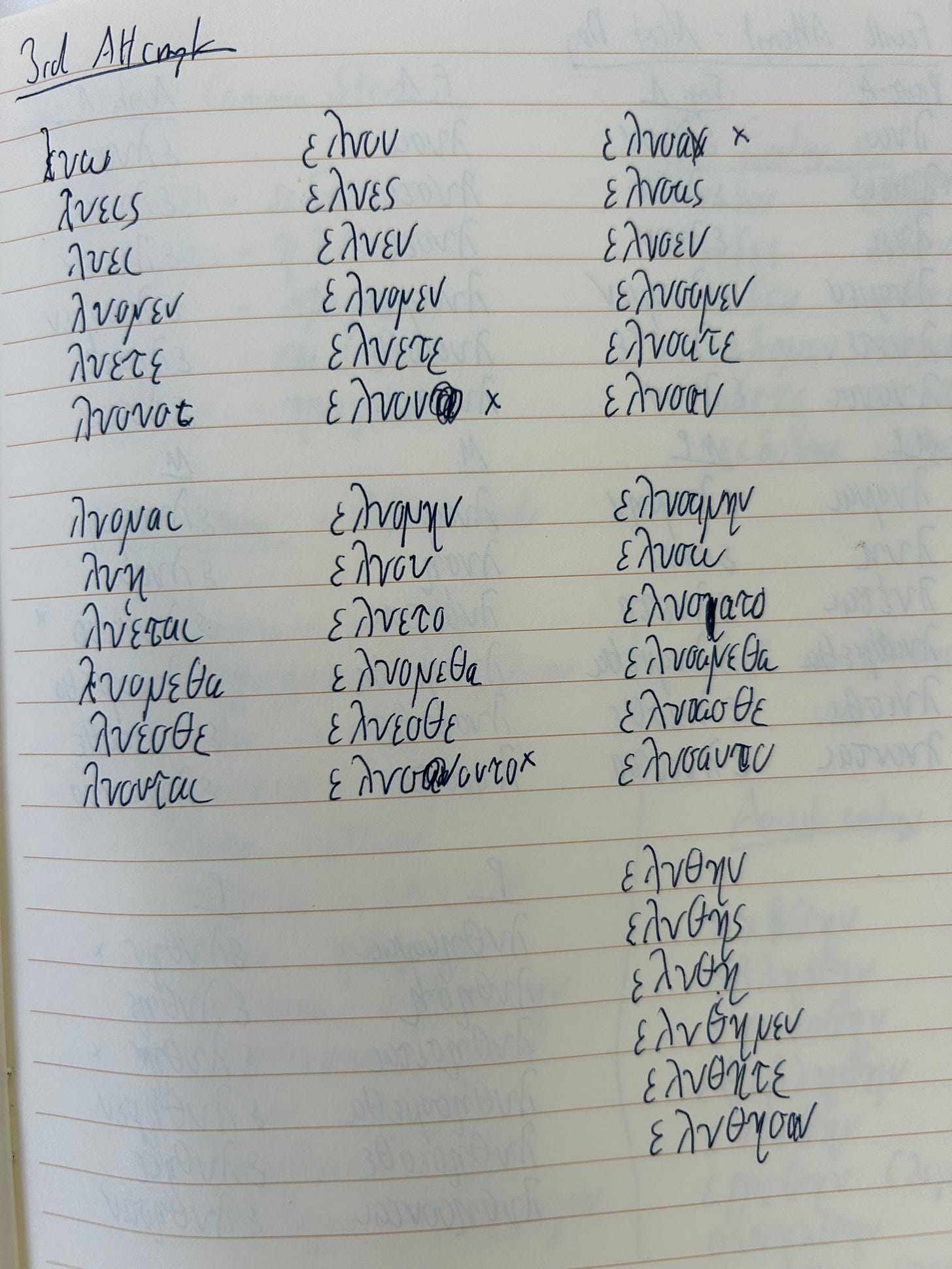

The fourth and final attempt, which I did the next morning, has everything laid out correctly, with three just mistakes. At that point I decided to give myself a break and wait another week or two before I tried again.

I should have anticipated my reward for this labor, but it still caught me as a pleasant surprise: when I went to translate sentences the next morning, it had become easier—and it has only grown easier since then. I promise that I am not exaggerating that statement to make a point. It was a marked difference in fluidity. Committing the forms to memory enabled and supported the more cognitively challenging work of translation, which we could describe as an act of interpretation and creativity.

Memorizing things is not fun. Grinding at a fundamental skill is boring. Trying and failing at something is frustrating. Because these learning practices are not always enjoyable, we can be tempted to argue against their importance or position ourselves as the innovators who will build a new educational world without them. I see a lot of that happening around me now, even in the ideas and arguments whose work I otherwise admire. I don’t want to shut down innovation, creativity, or educational technology. I do see a lot of value in traditional schooling practice, but I am always grateful to the people who push me to grow and change.

But I will finish with this. I have dedicated my life to learning, I know how it works, and learning Greek brings me small joys every day. And yet it took me like two years to heave a deep sigh and finally commit myself to doing the hard thing. This fact is what keeps me up at night these days, as I think about the future of learning, and the long-term impact of artificial intelligence on our students. I have this constant fear, as AI continues to spread through the education world, that we are engaged in a collective act of ladder pulling. We did the hard and boring stuff to get to where we are now, and some of us now are either allowing or suggesting that students shouldn’t waste their time on that stuff anymore.1

So I return to the question I posed above. As you think about your slow mastery of your field, developed many years of study and practice, what were the menial and painstaking tasks that contributed to your development? Would you still have achieved the same level of mastery without them? And if we allow students to offload those tasks to technological tools, what impact will it have on them?

Are we setting up ladders for them to reach new heights—or are we pulling them away?

I am speaking here about the use of AI to replace fundamental cognitive work, not supplement or enhance it. The recent survey of student uses of AI in Inside Higher Ed painted a hopeful picture, in that many students were using it to explain concepts, provide tutoring, or create study aids. We should support those uses and educate students about them.

I loved reading that part in your book about philomathy--in part, because one of my favorite songs is R.E.M.'s song "Can't Get There From Here," which includes the line, "When you're needing inspiration, Philomath is where I go." Philomath is, indeed, a very small town in Georgia, and I found a tshirt reading "Philomath, Georgia" on the internet that I bought and now enjoy wearing as a very obscure music reference. After reading your book, I also now sometimes put it on to write in, if I'm needing extra inspiration. (Minor costuming helps me a lot with writing. I have a black watch cap that I sometimes wear when writing, after reading Patti Smith talk about her writing uniform including a black watch cap.)

Your post has me thinking about when I took Latin in college. I had taken French in high school, and Latin was very new to me. I made so many flashcards of declensions and conjugations. One thing that helped me was color-coding the flashcards by declension or conjugation. The activity of writing out the flashcards and color-coding did help my learning. So did trying to find something extra to try to make it fun.

I realize that I am bordering on sounding like Principal Skinner in the Simpsons episode, where he talks about trying to "make a game!" out of tedious work. However, it sometime can help. And as you point out, so does actually seeing progress after practice. Learning to play the guitar has certainly been driving that point home to me lately. If I practice, I improve!