My Randomized Book Shelves

A love letter to my physical books and my disordered shelving habits.

I have been remiss this fall in terms of sticking to my monthly schedule for posting here, but I have a decent excuse: the Lang family is on the move. We have sold our family home, which was large enough to accommodate seven of us, and have bought a condo, which is the right size for two of us and maybe one trailing child as needed. (We currently have one living at home while she finishes graduate school, and when she leaves a graduating senior might replace her).

I wish I could tweak a phrase from Treebeard the Ent in The Lord of Rings by saying that this will be the “last march of the Langs,” but that seems unlikely to be true. We have lived in this house for ten years. We lived in the prior one for nine years, and six years in the one before that. Our stay in any dwelling seems to lengthen after each move, but I know us well enough to say that we will not be riding this condo into the sunset. My wife and I are a good pair in that we both seem to enjoy stability for a few years and then we itch for change: new houses, new schools, new adventures.

In preparation for this upcoming move, I have begun packing my books, which are shelved along an entire wall in my home office: five cases, stacked floor to ceiling, holding 27 shelves. I have another free-standing case on one of the side walls, with five shelves, and another full case in the living room with my hardcover books. Finally, I have a half-dozen boxes of books that I brought home from my office when I left my previous institution and which have been languishing in the basement.

Lots and lots of books, demanding a lot of packing time, but I am gloriously happy that our new condo has a finished library in the basement which has more shelves than I have in this house. Those neglected titles from my office, boxed away for four years, will emerge, blinking and astonished, into the lights of my new home office in just five weeks.

Holding all of my books again, title by title, has been a constant source of nostalgia, reflection, and inspiration. Sometimes a title will bring back memories of where I bought or read it; others prompt me to reflect upon big questions that I have left fallow in my brain in recent years; others set a spark burning to launch new projects, or return to half-finished ones. I am enjoying those feelings so much that I feel like I should just pack and unpack my books every few years to experience them on a more regular basis.

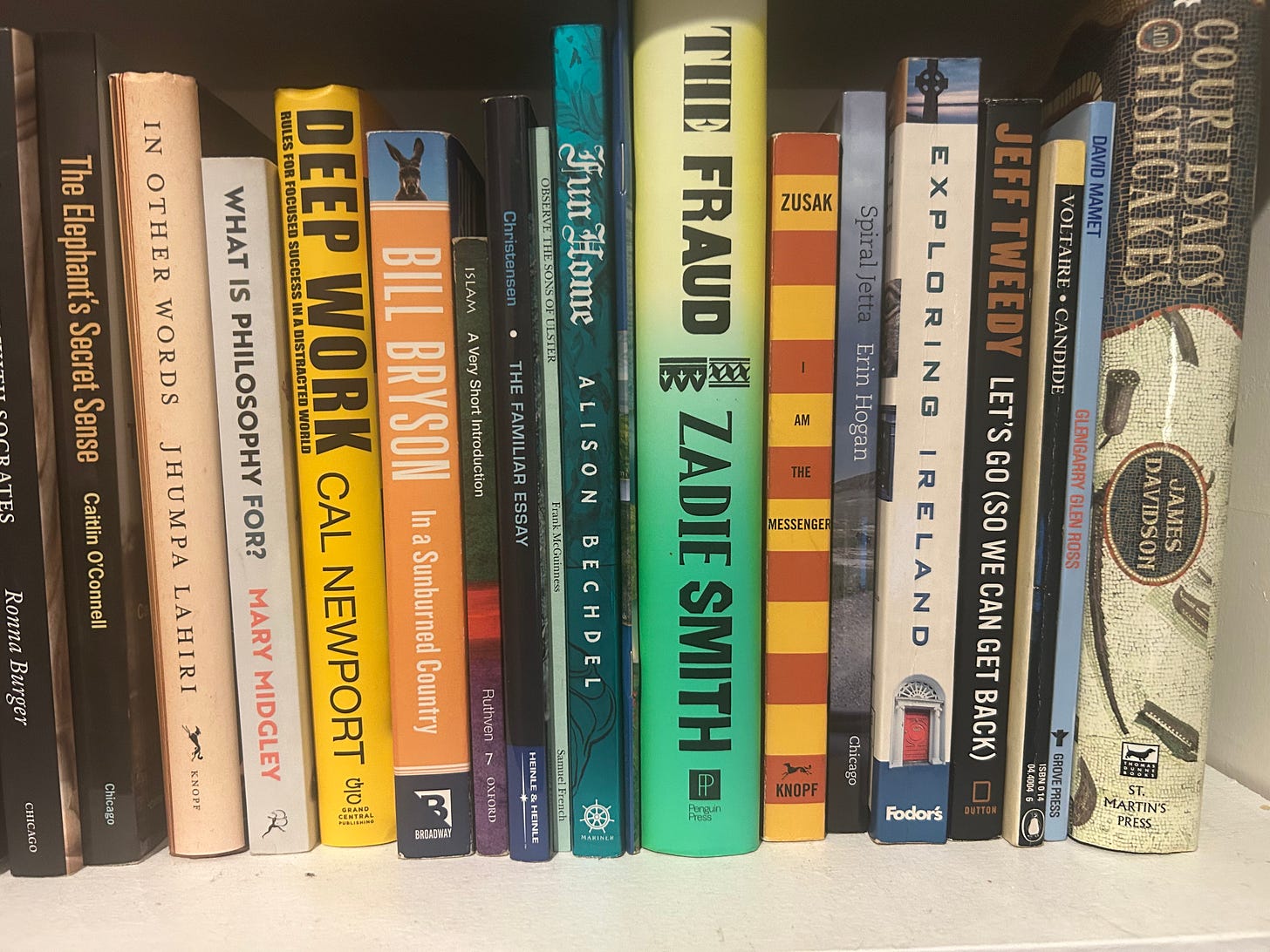

Or just re-randomize a few shelves every year. Re-randomize, because my lifetime’s approach to “organizing” books has always been to shelve them randomly. I like finishing a writing session or Zoom meeting, glancing at the shelves, and noticing a book that I haven’t thought about in a long time, and decide to re-read it (or even read it for the first time, because I certainly buy more books than I read).

I have, however, discovered one consequence of owning a lot of books and having no system of organizing them: I own duplicate copies of multiple books. I have only packed maybe 25% of my books, and I have already discovered five duplicate titles. Worse still, I own three copies of one title, which feels being slightly too cavalier about my disorganized approach to life.

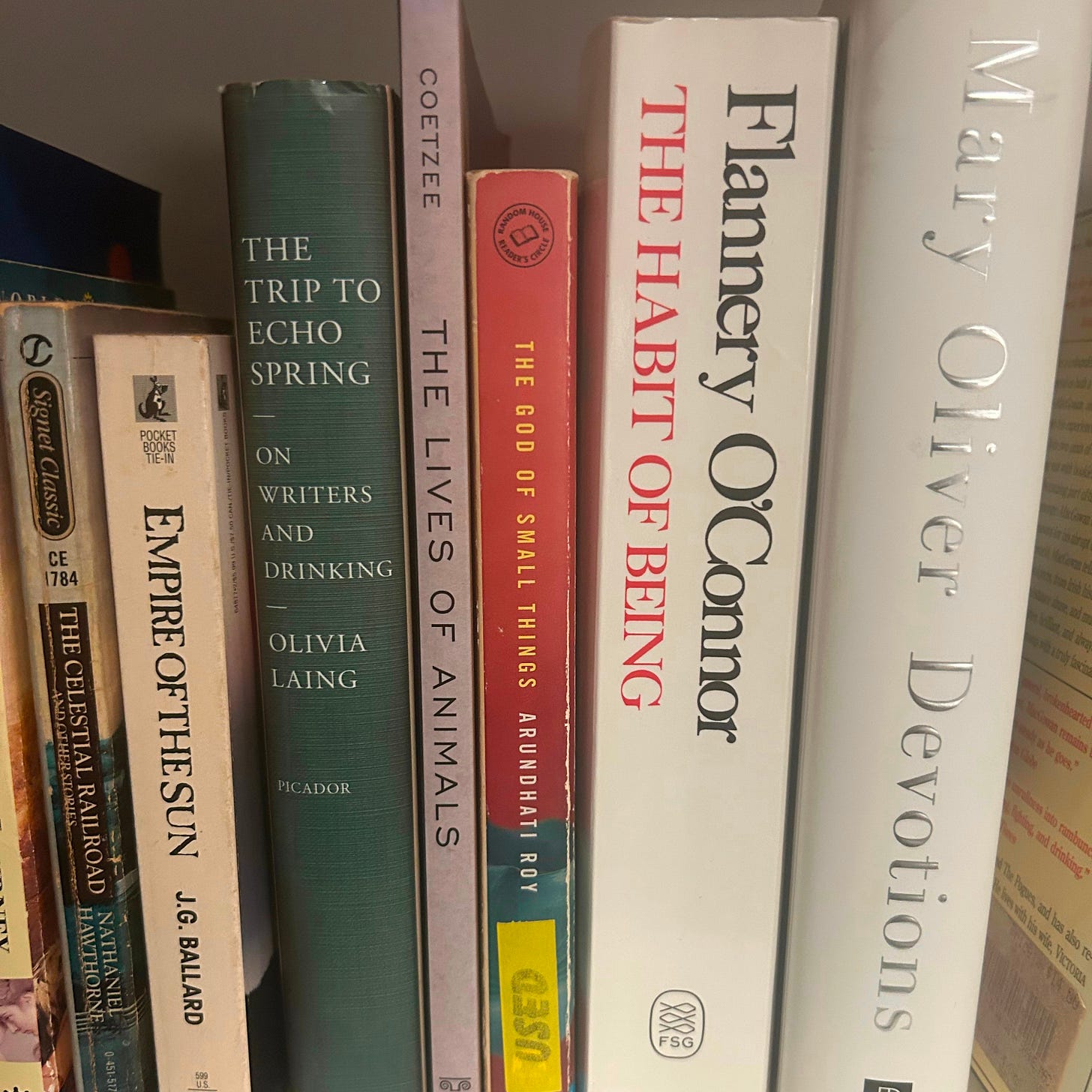

When people ask me what my favorite novel is, I usually say I have two: Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. My bookshelves have revealed the truth about my favorite novel, because I own two copies of White Teeth and three of The God of Small Things. Congratulations, Arundhati Roy.

Owning three copies of Roy’s novel is not just a random occurrence. It probably happened because I taught that novel a half-dozen times, and maybe just forgot to bring my novel to school one day, ran to the bookstore, bought another one, and forgot to return it—and maybe that happened more than once. In fact, when I think about The God of Small Things, it gives off this hazy impression of a classroom, as I and a group of senior seminar students navigate through its dense, poetic prose, searching for themes and developing interpretations.

Paging through one of those three copies again now, all marked up with my class notes, I remember some of the ideas we discussed. I recollect with sadness the fate of little Sophie Mol, and the pall it casts over everyone and everything in the novel.1 I marvel again at the beautiful craft of Roy’s sentences and startling word choices. I box away two of my copies of the novel, and put the third one on my list of books to re-read over the winter break. I wonder what memories, reflections, and ideas my next reading of that novel—maybe my tenth?—will inspire.

I am a cheerleader for books in any form: print, audio, digital. As long as people are reading books, I truly don’t care what form they take. In my last post in this space I described my experience of listening to David Copperfield. But my personal preference is for print books, for the exact reason that their materiality, their thingness, creates more possibilities for their resurrection, even after they have been long neglected on the shelf or in their boxes in the basement. Their return to my consciousness, and their potential to re-occupy space in my brain, might not happen often, but it does happen, largely because of their physical presence.

I have dozens of audio books in my listening app, and I don’t have to scroll through them in preparation for a move. I don’t have to touch or handle them. The same is true for the books (and manuscripts) that I have on my devices. They will move to the condo housed within the tiny real estate of my laptop. I never really have to see them again unless I go looking for them.

The books on these shelves in my office, their numbers already somewhat decimated by the moving process, put themselves into my face as I pack them into boxes, see them in the background of my Zoom calls, or go looking for a title for some reason and notice the ones shelved next to them. More than anything else, I value those random encounters when a printed book calls out and says “Hey, remember me?”

Because in those calls the unexcepted might happen. For example, an encounter with a book can spur me to renew or make a new connection, both intellectually or personally. One of my daughters has been reading more literary fiction as of late, and I handed her one of my three copies of The God of Small Things when she was home for Thanksgiving. I told her how much I have loved it, and I’ll follow up to see what she thinks over the winter break.

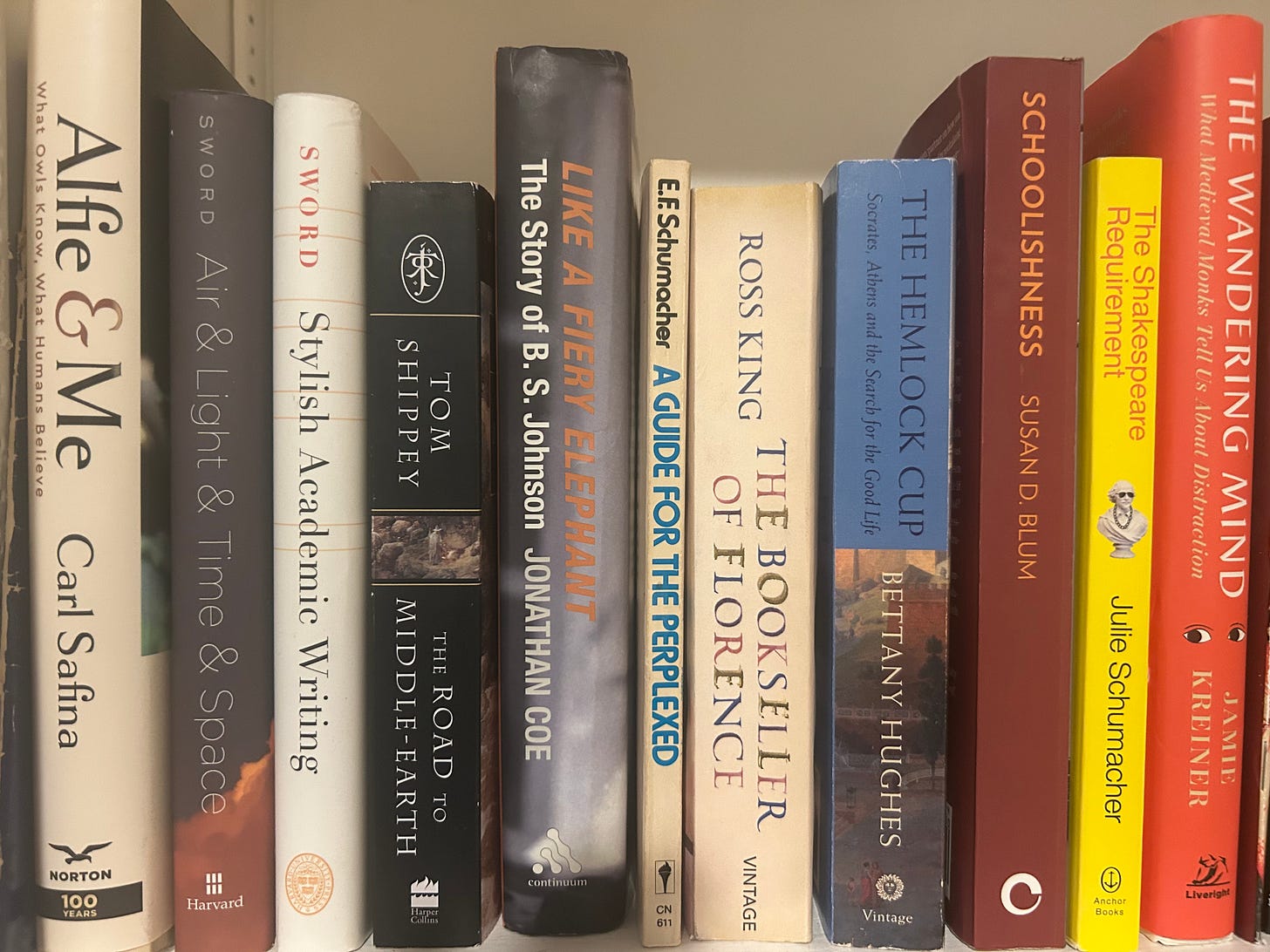

Seeing one book in proximity with another on the shelf can also spark a new idea about how I might insert a new perspective into a current project. Could that biography of experimental British novelist B.S. Johnson, written by another great British novelist, Jonathan Coe, somehow speak to my book-in-progress about reading? Or what would happen if three of the authors on the shelf in the above image—Helen Sword, Susan Blum, and Julie Schumacher—also jumped into that book project, or even into the same chapter, and pushed my thinking back and forth a little bit, unsettling my plans and pointing me into a new direction?

Having my thoughts pointed in one direction, and having them derailed into a new one, is actually the best recipe I know for maintaining a vibrant intellectual life, whether that comes to thinking, reading, or writing. We humans get settled too easily into our familiar places, and curious and learning minds needs to knock down the fences once in a while and find themselves standing, blinking and astonished, on some unfamiliar ground. My printed books, on their random shelves, remain as my most reliable transports into new territories.

My holiday wish for everyone is that someone gives you a book as a holiday gift, and that you give one to someone else. (You won’t go wrong with The God of Small Things.)

See you in January from the new condo.

This is not a spoiler—the reader learns about the death of Sophie Mol in the first few pages.

Love how this essay reframes what seems like chaos into a deliberate intellectual stratgy. The idea that random shelving creates those "Hey, remember me?" moments is basically engineered serendipity for the mind. Most productivity systems over-optimize for retrieval, but there's real cognitive value in being surprised by waht's already in our collection. The physical act of moving books almost functions liek a forced review session where ideas get reshuffled and new combinatinos emerge.

I have over 300 books and just gave away 300 books and I organize my books by discipline . So anthropology , china, Hong Kong , oral history , theory , methods, poetry, fiction, graphic novels , gender ( asian women ) and globalization is my division. I sometimes have 6 copies of one book.