Malcolm X on a Life of Learning

Themes, Images, and Questions from The Autobiography.

(Re-)Discovering the Autobiography

Last week I attended the Inclusive Teaching Academy sponsored by the Kaneb Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Notre Dame, which was held at a hotel in downtown Chicago. In preparation for the week, I had revisited some of my favorite books and resources on inclusive teaching, including Inclusive Teaching and the Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching

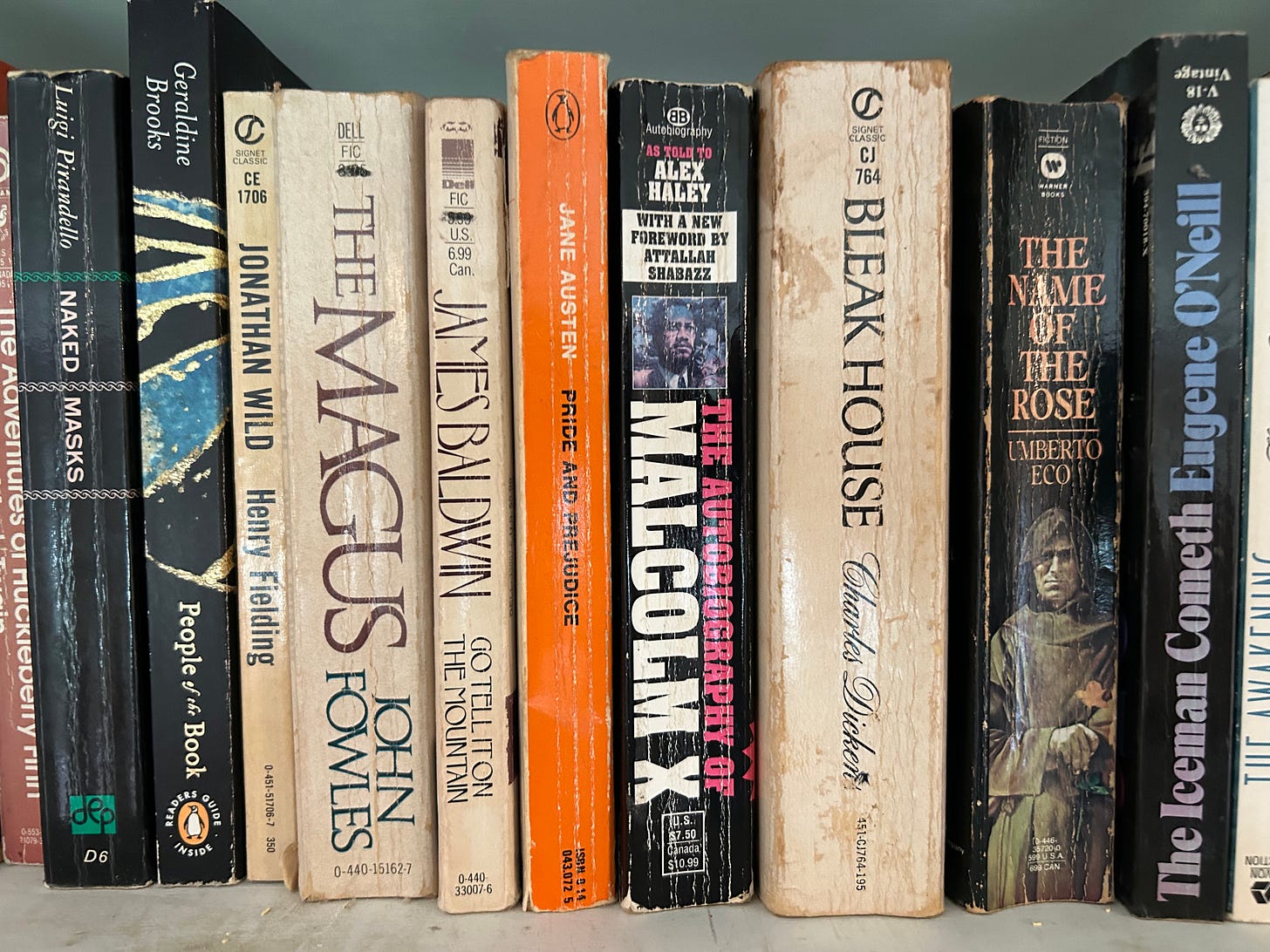

But in the spirit of this Substack, and in my general turn towards classics, I scanned my bookshelves before I left to see if I could find a book that would shore up the foundation of my learning about the roots of inequity in the United States. On the highest shelf, in the company of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, I noticed a book that I have owned for a very long time, but never read: The Autobiography of Malcolm X, “as told to” Alex Haley, who also wrote a long Epilogue.

I pulled down the book, which was clearly a used copy, because it has highlighting in it, and I have never been a highlighter. After reading it throughout my Chicago trip—on the plane, in my hotel room at night, on the CTA—I felt doubly grateful to the Inclusive Teaching Academy: first for the great ideas from its facilitators and participants, and second for giving me a reason to read The Autobiography. Spending time with Malcolm X shaped my thinking in new ways, and gave me new questions to pursue both in teaching and in my own learning.

Prior Knowledge

My prior knowledge of Malcom X, largely drawn from popular history, consisted of seeing him at one end of a spectrum in terms of how Black Americans should achieve equality, with Martin Luther King, Jr. at the other. These two men represented the far edges of binaries: violence vs. non-violence, explosive rage vs. righteous anger, revolution vs. gradual change, hate vs. love. Especially as you read about his time in the Nation of Islam, this perception of Malcolm X largely holds true.

But I was less aware of the turn that he took, at the end of his short life, away from the Nation’s peculiar take on Islam and the leaders to whom he felt intense loyalty. After a break with the Nation’s leadership, Malcolm X made the pilgrimage to Mecca, followed by extensive travels in Africa. His exposure to traditional Islam, and to the global nature of its adherents, gave him a more expansive vision of what could be accomplished through cooperation between America’s Black and white peoples.

The only note I feel qualified to make on the major theme of the book—racial inequality and equality in the United States—is that many of the problems that he documents in the 1950s and 1960s in America persist today. This reader could identify more parallels than contrasts between the racial tensions between Malcolm X’s era and our own. But at the end of the book, Malcolm X laments that people only want to think about or hear from him when it comes to race. He had many other interests, and he loved intellectual discussions on every subject.

I hope I am honoring his wishes, then, by articulating a very different theme from The Autobiography, one that makes the book an important read for teachers and learners in 2024: learning.

Learning in—and from—the Autobiography

I can’t think of another book which documents so well a mind dedicated to learning, and the consequences of learning in shaping a human life. Malcolm X left formal schooling early in his life, which means that he had to discover learning pathways in almost random fashion, as autodidacts often do. But because his mind was so firmly directed toward learning, his story reveals how various modes of learning helped him in different places and times in his journey.

To be sure, he did some learning in his school years and when he hustled on the streets. His more conscious, dedicated learning begins in prison, initially through his devouring of the books in the prison library. But he explains that in every book he tackled, he encountered word after word that meant nothing to him. As a result, he says, “I really ended up with little idea of what the book said,” “going through only book-reading motions.” He had a street-hustler vocabulary, and not much more than that. While this limitation interfered with his reading, it especially stymied him in his efforts to write letters to people outside of prison.

To combat his limited vocabulary, Malcolm X does an extraordinary thing. He asks the prison for a dictionary and some writing implements. Overwhelmed by the volume of words in the dictionary, and unsure of where to start his learning, he begins by transcribing the first page:

In my slow, painstaking, ragged handwriting, I copied into my tablet everything printed on that first page, down to the punctuation marks. I believe it took me a day. Then, aloud, I read back, to myself, everything I’d written on the table. Over and over, aloud, to myself, I read my own handwriting.

After rolling the words on the first page around in his mind for a day, he copies the next page. And the next one, and the next one, until he makes it through the entire dictionary.

I can’t think of a learning practice that would be less recommended by an educator today than copying out the dictionary and reading it aloud to yourself, including every punctuation mark. And yet the fruits of this work are evident if you watch or read any of Malcolm X’s speeches; his command of the language is a marvel. The constraints of his prison cell forced him into a rote method of learning, but his curious mind and his motivation to develop a new skill made it work.

At the end of his life, in possession of both liberty and international fame, Malcolm X turns away from the Nation of Islam to the traditional Islam that has been calling to his spirit, and makes his pilgrimage to Mecca. There, with the support of many people in the Middle East and Africa, he has another mind-expanding experience: seeing racial relations outside of the United States context. He had learned, and even taught, the Nation of Islam’s strange mythology of the origins of the races, and preached on countless occasions that all white men were devils. On his travels, he discovers humans of every race treating one another as full humans.

A person whose primary orientation was toward their convictions would have found a way to ignore these experiences, or twist them to make them confirm to their firmly held beliefs. Malcolm X, the learner, was not such a person. Well aware of how the lessons from his experiences abroad would astonish his many followers in the United States, he wrote a public letter to them which included this paragraph:

You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This was not too difficult for me. Despite my firm convictions, I have been always a man who tries to face facts, and to accept the reality of life as new experience and new knowledge unfolds it. I have always kept an open mind, which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth.

Through his travels, Malcolm X discovers the power of experiential learning—taking the ideas he has learned from his books, his teachers, and his local experiences to a new context, where they are challenged and expanded. Most teachers today would recognize the power of experiential learning, and endorse it at least in theory, even if they don’t always practice it in their courses. It aligns well with other progressive pedagogies, and has plenty of theory and research behind it.

And it worked for Malcolm X—but so did a variety of other learning methods discussed in the book. He describes learning from formal schooling, mentoring, reading, debating, studying the techniques of experts, and more. The critical features carried through all of these experiences were less the learning technique and more his deep curiosity and an open mind. With those two qualities, he found varying ways to learn that matched his circumstances and the goal: learning to write and speak by copying the dictionary in a prison cell, for example, and “studying abroad” to expand his vision of what might be possible in a more just society. He was an adaptive learner, moving across systems and practices in the pursuit of the truths he sought.

If I have any conclusions to draw from that analysis, it would be that sometimes I think teachers—especially those of us in higher education—spend too much time trying to identify the ideal teaching techniques that will work for all students. I made a similar argument in the Chronicle of Higher Education recently. Not only does this aspiration for teaching perfection not acknowledge the complexity of every teaching context, it also makes us lose sight of the incredible agility of the human brain, which can find ways to learn even when we put barriers in front of it. The quality and care of the support we provide to learners might matter more than the chosen techniques that guide the process.

But I won’t put my stake on the ground on that conclusion, or any other conclusion from my reading of Malcolm X’s life, because mostly it left me with images and scenes. The one that I can’t stop thinking of is this: a young Black man, sitting in a prison cell, slowly copying pages from the dictionary. And the questions follow: What can I learn from that? How does it challenge my long-held notions about teaching and learning? What would I say to students or teachers in 2024 about it?

A Tragic Ending

Of course the life of Malcolm X has a tragic ending, when some followers of the Nation of Islam shot him on stage at a Manhattan ballroom. That story is told in the book’s Epilogue, written by Alex Haley. But for me the saddest moment in the Autobiography comes in its final pages, when Malcolm X laments his lack of academic training, and expresses his desire to keep learning new things. “For example,” he says,

I love languages. I wish I were an accomplished linguist . . . In Africa, I heard original tongues, such as Hausa, and Swahili, being spoken, and there I was standing like some little boy, waiting for someone to tell me what had been said: I will never forget how ignorant I felt.

But then, ever Malcolm X the learner, he says

Aside from the basic African dialects, I would try to learn Chinese, because it looks as if Chinese will be the most powerful political language of the future. And already I have begun studying Arabic, which I think is going to be the most powerful spiritual language of the future.

One can consider many aspects of the life of Malcolm X tragic, but for me none more than what you read in these final passages: a curious mind, eager for new learning, ready to expand his knowledge. He would be assassinated within the year,

Malcolm X had so much still to learn—and we still have so much to learn from him.*

*I don’t want to ignore two unsavory features of the Autobiography; its antisemitism and its stereotypical comments about women, which can be borderline misogynistic. These are especially prominent in the early parts of the book, but they still taint the final chapters. I would love to think that Malcolm X’s dedication to learning, and his ability to change his mind, would have led him eventually to abandon those prejudices.

Wonderful reflection. I remember picking this book off my parents' bookshelves when I was in high school, read it on my own, and then occasionally using it to argue with a teacher who seemed to have it in for Malcolm X. If you haven't seen it, you might be interested in this story from Jonathan Eig's MLK biography from last year, in which he discovered that a famous criticism of Malcolm X by King was fabricated. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/may/10/martin-luther-king-jonathan-eig-book-malcolm-x