Knowledge, Old and New

Liberal-Arts Thinking on Higher Education

For more than a decade now, I have been editing manuscripts for a book series on teaching and learning in higher education. That series promises that our titles will be informed by the latest discoveries on human learning, which might draw from fields like cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and education. We expect our authors, in other words, to do their research. When I co-founded the series, I believed in the value of this promise, and I still do.

Not too long ago, I was reviewing some reader reports that noted that an author was basing their conclusions on neuroscience that was of a vintage of a dozen years vintage or more. Our understanding of the brain has been moving so quickly in recent years, the reader pointed out, that the author needed to ensure that their ideas correlated with what brain scientists have discovered in the past decade. I completely agreed with the reader. When you’re writing about brains, you need to be on top of the latest developments in brain science.

This criticism, though, reminded me how far I have traveled from my degrees in English and philosophy. While literary scholars and philosophers are expected to address recent developments in their fields, we also don’t shy away from valuing and engaging with scholarship and texts that date back decades, centuries, and even millennia. Scientists of natural and social phenomena put much more of a premium on recency in their research, which makes sense. The tools of their fields—data-crunching programs, technologies of observation, artificial intelligence—have enabled them to deepen our knowledge at a head-spinning pace.

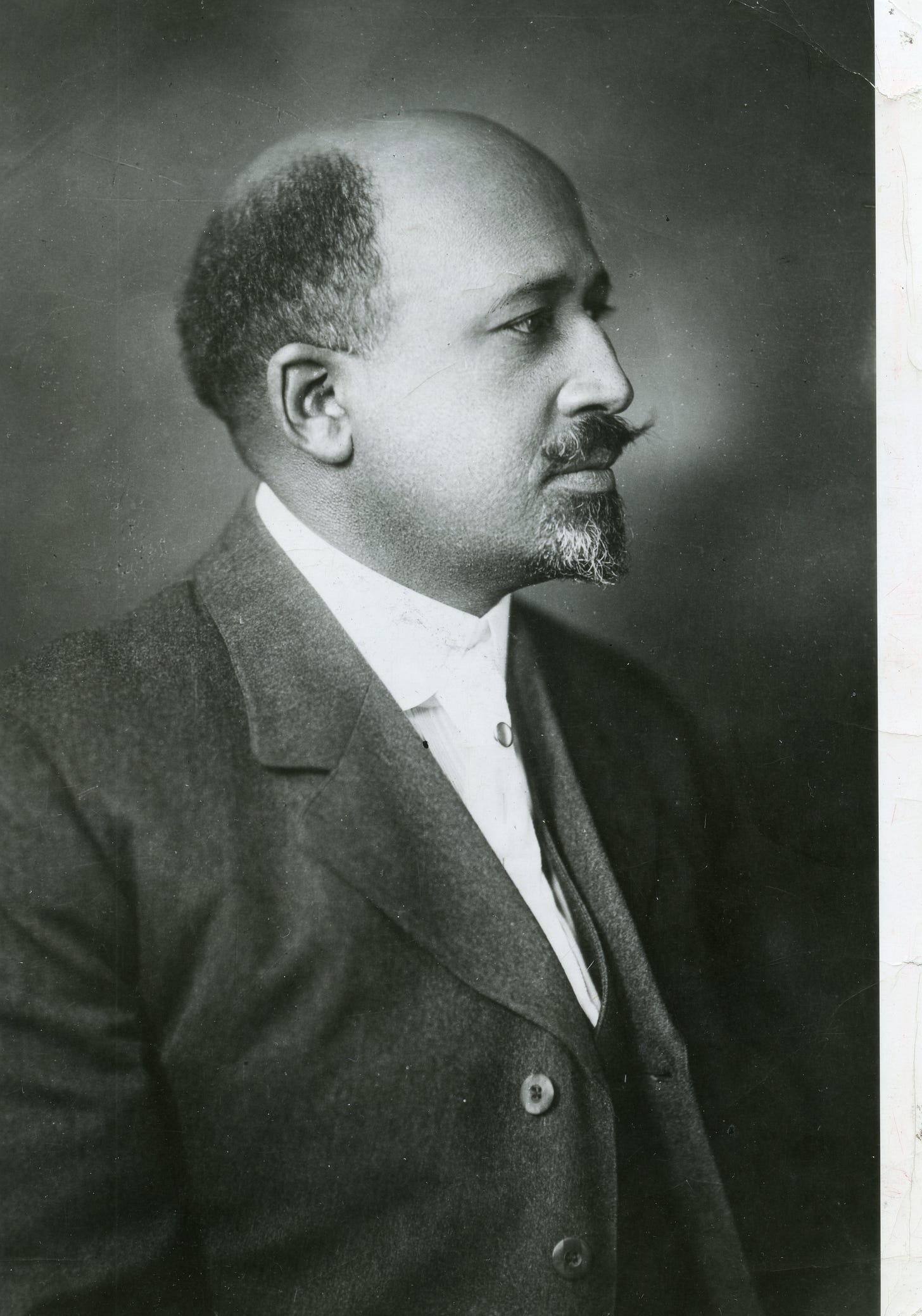

At the same time I was processing that reader’s report, I happened to be reading W.E.B Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folks, a collection of essays first published in 1903. Now a century old, this text remains a towering literary and philosophical achievement in which Du Bois analyzes the failures of America to provide black people with the freedom, safety, and opportunities that the outcome of the Civil War promised. I was drawn back to The Souls of Black Folk after listening to two episodes from the Norton Library Podcast, which features interviews with the translators and editors of classics work published by W.W. Norton. Those episodes feature a two-part interview with Harvard’s Jesse McCarthy, who edits a new edition of the book.

In response to a question from the interviewer about the continued relevance of Du Bois’s writings, McCarthy argues that older works like The Souls of Black Folks must be interpreted in their historical contexts, but also have portable themes that can extend beyond their originating moments. We should not read Du Bois for life lessons, for example, without acknowledging that he was addressing the specific injustices faced by black people in America at the opening of the 20th century. At the same time, Du Bois offers words, phrases, and ideas that can put shape to our thoughts today, and invite us to step back from the tangles of our age and find new entry points to our current debates.

I felt this in my reading of every chapter of The Souls of Black Folk, especially when he wrote about education: its promises, its achievements, its failures. The currency of his insights astonished me. In a chapter entitled “The Training of Black Men,” he writes about what we have been calling asset-based pedagogy in recent years: “the longing of black men must have respect: the rich and bitter depth of their experience, the unknown treasures of their inner life, the strange rendings of nature they have seen, may give the world new points of view and make their loving, living, and doing precious to all human hearts.” Instead of treating black people as deficient humans in need of remedial education, Du Bois argues, America should not only honor their distinctive histories, but recognize that their experiences and intelligences offer insights, expertise, and perspective that add to the store of our common knowledge.

Today’s scholars of pedagogy have made parallel arguments about how traditional educational practices take a similar deficit-based approach to many students, including those who have experienced opportunity gaps or bring their neurodivergent brains onto our campuses. Focusing on the deficits of such students eclipses the assets that they bring to the learning process, not to mention to the learning of their peers and teachers. The ADHD student who has learned to navigate through a traditional education system can reveal the cracks and injustices that others can’t perceive, just as an indigenous student might inform and expand the views of professors and students with her insights into educational inequality in America.

To be sure, teachers who seek to evolve their teaching from a deficit-based approach to an asset-based one can find plenty of resources and ideas in the articles and books published in the last few years. As someone who both teaches and writes about teaching, I want to engage the work of these emerging and established scholars, especially as they write in the context of our present moment, in an era of pandemics and climate change and artificial intelligence. I value and benefit from the scholarship produced by today’s scientists of every stripe, especially in the fields of learning and teaching.

But I also want to acknowledge the heritage of the questions and concerns that we debate today, and—more importantly—discover how older writers like Du Bois might offer us intellectual assets that illuminate our current questions in unexpected ways. As we reach backward in time and across traditions, we might find ourselves jarred into productive new approaches to our current work by the gaps in time, place, and culture. Just as a student from an under-resourced high school can raise her hand and startle an expert chemist with a sharp question based on her own experiences, so can a lonely author’s voice cry out with clarity from beneath the accretions of modern scholarship.

In this Substack newsletter, which will appear on a monthly basis, I’ll highlight texts from writers and thinkers from across different traditions of thought and culture, especially philosophers, theologians, novelists, poets, political theorists, and more. The goal for each post will be to expose and analyze an idea from a humanities text that has resonance for the questions faced by higher education today. While I will reach back into ancient traditions, I will also feature modern classics. We have as much to learn from the miseducation of Irie Jones in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth (published in 2000) as we do from Roman philosopher Seneca’s letters to a younger friend (composed circa AD 65).

I close with one final inspiration for this blog, which comes from medicine. Tu Youyou was a Chinese scientist who led an effort funded by the Chinese government to discover a cure for malaria. She achieved that incredible medical milestone without an advanced degree or formal medical training. She led her research team along the path to the cure began by revisiting the ancient texts of Chinese medicine, where she read about the use of a specific plant to treat fevers. Working forward from there, she and her collaborators developed a treatment that she first tested on herself, and then offered to others—all of whom were cured. In 2015, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work in tapping this body of traditional wisdom and putting it in dialogue with modern scientific methods, with such admirable results.

I won’t promise you anything as dramatic as a cure for malaria coming from this free Substack newsletter, but I hope you will join me in search of insights. We’ll put into conversation the ancient and the new, the classic and the modern, the mainstream and the outside. Subscribe below for one post a month, and share the link with others. This seminar table has plenty of seats, and all are welcome to the discussion.

October’s Post: How John Dewey’s ideas about the relationship between experience and education can guide our thinking about artificial intelligence.

Enjoy, comment, suggest future texts for discussion, and tell your friends.